A virus might trigger or contribute to Parkinson's disease, Northwestern Medicine researchers find

New research from Northwestern Medicine has discovered that a virus that is usually harmless could trigger or contribute to Parkinson's disease.

Parkinson's disease is a neurogenerative disease that affects more than 1 million people in the U.S. Speaking to CBS News Chicago on Tuesday afternoon, Northwestern Medicine chief of neuroinfectious diseases and global neurology Dr. Igor Koralnik said while some cases are caused by genetics, the cause is unknown in most.

"So what we wanted to do is to find out whether environmental factors such as viruses may be associated with Parkinson's disease in some cases," Koralnik said.

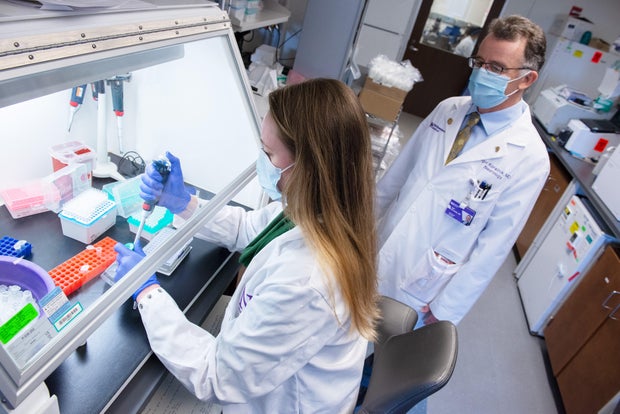

To solve that mystery, Koralnik and his team, including post-doctoral fellow Dr. Barbara Hanson, used a tool called "ViroFind," which can identify more than 500 species of viruses in clinical samples. With ViroFind, they examined the brain tissue of a group of 10 patients who had died of Parkinson's — as well as that of a group of 14 control patients who had died from other causes and did not have Parkinson's.

"And what we found in 50% of the cases of Parkinson's disease, the presence of this virus called the Human Pegivirus — which is otherwise not known to cause any disease. It's a harmless bloodborne virus — in the brain of the Parkinson's patients, but not in any of the control brain samples," Koralnik said. "We also found that the patients with Parkinson's disease who had the virus in the brain had a more severe pathology of Parkinson's disease, and we also found an alteration of immune signaling in the brain of those patients."

Human Pegivirus, or HPgV, was also found in the spinal fluid of the deceased Parkinson's patients — but not in that of those in the control group.

The Northwestern researchers also analyzed blood samples from more than 1,000 participants in the , which was launched by the Michael J. Fox Foundation and scientists to develop a biosample library. The blood samples showed similar immune-related changes associated with HPgV as the brain samples, Koralnik said.

The study specifically determined that in patients with a specific Parkinson's-related gene mutation, LRRK2, the signals in the immune system were different in response to HPgV compared to those who do not have Parkinson's.

Currently, there is no test to determine whether people are carrying Human Pegivirus. Nevertheless, the study could have ramifications for Parkinson's treatment down the road.

"This is opening a new field of research — which we think is very intriguing and interesting, since the Human Pegivirus is a close relative of another virus called the Hepatitis C virus, for which medication is already available to target the virus in the liver," Koralnik said. "So if this is confirmed — and we're doing further studies to confirm and expand those initial findings — it would be potentially possible in the future to repurpose those medications for the Hepatitis C virus to also target the Human Pegivirus in the brain. But at this point, it's too early to tell."

The Northwestern Medicine researchers' findings were published in the July 8 edition of the journal .

Future research will also seek to determine how common HPgV actually is in Parkinson's patients, and whether it indeed plays a role in the disease.