Texas agriculture commissioner dismisses cloud seeding conspiracy theories after Central Texas floods

The Texas Department of Agriculture is not conducting weather modification, Commissioner Sid Miller said Wednesday, addressing what he describes as false claims circulating on social media in the wake of the devastating Central Texas floods.

"There has been a lot of misinformation flying around lately, so let me clarify: the Texas Department of Agriculture has absolutely no connection to cloud seeding or any form of weather modification," Miller said .

, the Department of Agriculture has had no legal authority, responsibilities, or involvement in any weather modification programs.

"That authority was transferred out of our hands more than a decade ago," Miller said.

"Weather modification and control," , means "changing or controlling, or attempting to change or control, by artificial methods the natural development of atmospheric cloud forms or precipitation forms that occur in the troposphere."

Miller said that as an eighth-generation farmer and rancher, he turns to faith when faced with a drought.

"Let's put an end to the conspiracy theories and stop blaming others," his statement read. "Our priority should be the recovery efforts in the Texas Hill Country, as we stand in solidarity with our fellow Texans."

Is Texas modifying the weather?

Yes and no.

The Texas Weather Modification Act, now codified as Chapter 301 of the Texas Agriculture Code, was enacted in 1967 by the state Legislature, and state-funded cloud seeding programs began in the late 1990s.

The state directed agencies to disburse funds to municipalities, like water districts and county commissions, for cloud seeding operations, primarily in drought-stricken areas.

Initially, the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission dispensed funds. The Texas Department of Agriculture took over in 2001 and in 2003, the Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation took up the charge.

The act requires the through a licensing and permitting procedure. It also charged the TDLR with promoting the development and demonstration of cloud-seeding technology through research.

From the time the State began paying in part for the programs until State funds were exhausted in 2004, Texas contributed about $11.7 million.

What is cloud seeding? Is it happening in Texas?

According to TDLR, projects have since been funded by underground water conservation districts and other local political subdivisions, like county commissions and aquifer authorities.

"Cloud seeding is a technique used to improve precipitation. According to the Desert Research Institute, scientists do this by putting tiny particles called nuclei into the atmosphere that attach to clouds."

"These nuclei provide a base for snowflakes to form. After cloud seeding takes place, the newly formed snowflakes quickly grow and fall from the clouds back to the surface of the Earth, increasing snowpack and streamflow," the institute said.

Cloud seeding cannot create clouds. It can enhance the rainfall produced by those clouds up to 20%, according to studies by the .

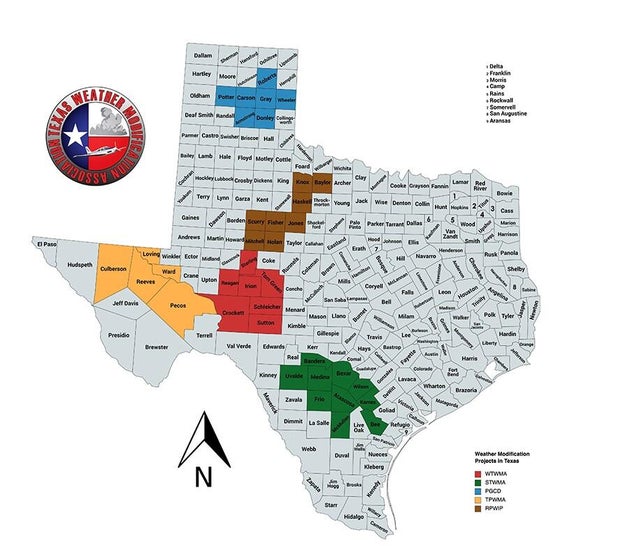

The TDLR said, "rain enhancement projects flourish within large areas of Northwest, West, and South Texas," and current "cloud seeding projects cover about 31 million acres, or about one-sixth of the land area of the state."

- The West Texas Weather Modification Association, based in San Angelo, holds permits for both rain enhancement and hail suppression operations.

- South Texas Weather Modification Association, based in Pleasanton, south of San Antonio, was established in 1997 to seed clouds from the base of the Edwards Plateau to near the coastal bend area of Texas. The weather modification project runs on a year-round basis, according to TDLR.

- Panhandle Groundwater Conservation District conducts cloud seeding operations over the Ogallala Aquifer in the state's northern extremity.

- Trans Pecos Weather Modification Association consists of the Ward County Irrigation District and other political subdivisions within Culberson, Loving, Pecos, Reeves, and Ward counties. Cloud-seeding has been underway west of the Pecos River since May 2003.

- Rolling Plains Water Enhancement Project includes around half a dozen counties sponsoring cloud seeding from near Abilene north and eastward toward the Red River valley.

The last cloud seeding operation in the south-central Texas area was on the afternoon of June 2, conducted by . Those clouds lasted for a couple of hours before dissipating, according to Rainmaker CEO Augustus Doricko.

Social media claims and the National Weather Service

Claims have been made on social media that cloud seeding is to blame for the catastrophic Fourth of July floods in the Hill Country region.

The lifespan of clouds is a few minutes to a couple of hours. Cloud seeding cannot create new clouds nor can it dump millions or trillions of gallons of water over an area, CBS News Texas Chief Meteorologist McKenna King said.

The area is known as "Flash Flood Alley." The terrain reacts quickly to rainfall. Steep slopes, rocky ground and narrow riverbeds leave little time for warning.

Texas hydrologists working with the National Weather Service said they recognized the conditions on July 3 that could lead to catastrophic flooding on the Guadalupe River.

And they said, based on past events, this kind of outcome was a known risk.

CBS News Texas' I-Team reviewed National Weather Service and historical crest records and found that the Guadalupe River has experienced major flooding more than a dozen times in the last century.

What caused the Central Texas floods?

This event was partly triggered by the remnants of Tropical Storm Barry that hit Mexico on Sunday, June 29, King said.

The atmosphere was loaded with water vapor from Barry that moved north into the middle parts of Texas.

More than a foot of rain fell in less than 12 hours, from July 3 to the morning of the Fourth of July.

The destructive fast-moving waters rose 26 feet in just 45 minutes before daybreak Friday, washing away homes and vehicles. The danger was not over as torrential rains continued to pound communities outside San Antonio on Saturday, and flash flood warnings and watches remained in effect.

Experts say the region's unique terrain and soil also played a role in turning the storm into a disaster.

"The Hill Country has very unique soil conditions," said Dr. Nick Fang, a civil engineering professor and flood infrastructure researcher at the University of Texas at Arlington. "The soil layer is pretty thin, and underneath is mostly granite and limestone. The ground just can't take in much water."

With nowhere to go, rainwater rushed across the surface, straight into creeks and streams, creating rapid flash floods with little time for residents to respond.